Jackie: It seems perfectly appropriate that the Manager of Holiday Placement has placed Valentine’s Day, a day to celebrate love and affection, right in the middle of cold, dark February. I want that celebration to spread out for the whole month (why not the whole year?) the way the smell of baking bread fills an entire house, not just the kitchen. Why can’t all of February be Heart Month? We are choosing books this month with that goal in mind. We want to celebrate heart, love, ties of affection. And we have chosen a new book, a couple of medium new books and an old book to help us.

A while back we did an entire column on Vera B. Williams. But I am still missing her. I need her political activism and her huge heart in my neighborhood. I turned to More, More, More Said the Baby. (Greenwillow, 1990).

A while back we did an entire column on Vera B. Williams. But I am still missing her. I need her political activism and her huge heart in my neighborhood. I turned to More, More, More Said the Baby. (Greenwillow, 1990).

This book is a huge celebration of the love between daddies and kids:

Just look at you

With your perfect belly button

Right in the middle

Right in the middle

Right in the middle

Of your fat little belly.

Then Little Guy’s daddy

Brings that baby

Right up close

And gives that little guy’s belly

A kiss right I the middle

Of the belly button.

Between grandmas and kids:

Then Little Pumpkin’s grandma

Brings that baby right up close

And tastes each

Of Little Pumpkin’s toes.

And mamas and kids:

Just look at you

With your two closed eyes

Then Little Bird’s Mama…

Gives that little bird a kiss

Right on each of her little eyes.

I never tire of reading about these children, diverse children, who are so loved and so valued. This book will be fresh as long as we laugh and kiss babies with belly buttons and ten little toes.

Phyllis:; I miss Vera B. Williams, too, and I love seeing her spirit still alive in her books and also in the hearts of people everywhere who care about people everywhere. Her language in More More More is so delicious – along with the repetition we have lively verbs of interaction between grown-ups and beloved children (swing, scoot, catch that baby up). Little Guy, Little Pumpkin, and Little Bird have names that could be any child’s. I love, too, the exuberant art and hand lettered multi-colored text. Everything about this book celebrates taking joy in our children.

Jackie: In My Heart Will Not Sit Down, (Alfred Knopf, 2012) empathy and caring for others travel around the world. Rockliff creates a school child Kedi, who hears from her teacher about the hungry children in New York City and cannot stop thinking about them. She asks her mother for a coin to send them. Her mother says they have no coins to spare. “Kedi knew Mama was right. Still, her heart would not sit down.” She asks an uncle, a sweeping mother with a baby on her back, a grandmother pounding cassava, laughing girls who carried pots of river water, old men playing a game of stones, even the headman. No one has coins… Until the next morning when her mama gives her one coin. She takes the coin to school, thinking that one coin can do little good for the hungry children. Then the villagers show up — each bearing a coin. “We have heard about the hunger in our teacher’s village,” said the headman. “Our hearts would not sit down until we helped.”

Jackie: In My Heart Will Not Sit Down, (Alfred Knopf, 2012) empathy and caring for others travel around the world. Rockliff creates a school child Kedi, who hears from her teacher about the hungry children in New York City and cannot stop thinking about them. She asks her mother for a coin to send them. Her mother says they have no coins to spare. “Kedi knew Mama was right. Still, her heart would not sit down.” She asks an uncle, a sweeping mother with a baby on her back, a grandmother pounding cassava, laughing girls who carried pots of river water, old men playing a game of stones, even the headman. No one has coins… Until the next morning when her mama gives her one coin. She takes the coin to school, thinking that one coin can do little good for the hungry children. Then the villagers show up — each bearing a coin. “We have heard about the hunger in our teacher’s village,” said the headman. “Our hearts would not sit down until we helped.”

Phyllis: This is one of those books that called to me from the shelf in a bookstore and captivated my heart once I opened it. Kedi’s heart stands up for the hungry children in New York, America, as she calls it. When the villagers bring their coins, which the author notes would be a small fortune to the village even though $3.77 would not go far in America even in the Depression, her mama asks, “Now will your heart sit down in peace?” Kedi answers, “Yes, Mama, Yes!” The author notes, too, that in Cameroon, where the event occurred on which the story is based, people shared with anyone in need, even strangers, because, as they said, “You may meet him [a stranger] again, and in his own place.” This story reminds me that the actions of one small person can touch many hearts and feed hungry children.

Jackie: Hearts can spur us to action. Hearts can break. And the last two books are gentle stories of the heartache of loss. Oliver Jeffers writes of a “little girl…whose head was filled with all the curiosities of the world.” Jeffers shows us this little girl talking with her grandpa who sits in a chair, lying under the stars with her grandpa. He accompanies her on all her explores. And then one day the chair is empty. She decides to put her heart in a bottle to keep it safe. After that she wasn’t curious. She grows up and the bottled heart is heavy around her neck. When she wishes to retrieve her heart she can’t — until she meets another little girl.

Jackie: Hearts can spur us to action. Hearts can break. And the last two books are gentle stories of the heartache of loss. Oliver Jeffers writes of a “little girl…whose head was filled with all the curiosities of the world.” Jeffers shows us this little girl talking with her grandpa who sits in a chair, lying under the stars with her grandpa. He accompanies her on all her explores. And then one day the chair is empty. She decides to put her heart in a bottle to keep it safe. After that she wasn’t curious. She grows up and the bottled heart is heavy around her neck. When she wishes to retrieve her heart she can’t — until she meets another little girl.

This is a story about dealing with sadness — we want to protect our hearts but we lose so much when we wall them up.

Phyllis: Oliver Jeffers both wrote and illustrated The Heart and the Bottle, and the illustrations help carry the events and the emotions of the story. When the girl who has bottled her heart decides as a grown-up to take her heart out again, the art shows her trying to shake the heart out, grip it with pliers, break the bottle with a hammer, and finally, abandoning her work bench covered with a drill, a cross cut saw, a wooden mallet, screwdriver, and other assorted tools including a vacuum cleaner leaning again the bench, she climbs a ladder to the top of an enormously tall brick wall and drops the bottle which still doesn’t break but just “bounced and rolled…right down to the sea” where a little girl easily frees the heart from the bottle and returns it. The book ends, “The heart was put back where it came from. And the chair wasn’t empty anymore. But the bottle was.” Here, too, the art reflects that the woman’s world is once again filled with wonder. We need our hearts within us.

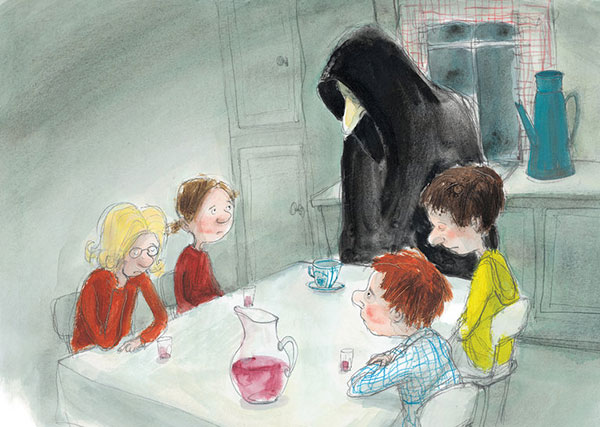

Jackie: Cry, Heart, But Never Break comes to us from Denmark. It was written by Glenn Ringtved, illustrated by Charlotte Pardi and translated by Robert Moulthrop (Enchanted Lion Books, 2016). This book also deals with loss. Four children live with their grandmother — “A kindly woman, she had cared for them for many years.” Then Death knocks at the door. The children decide to forestall Death’s mission with coffee. They will keep him drinking coffee all night so he cannot take their grandmother, thus giving her another day of life. Eventually he has had enough. And one of the children asks why grandmother has to die. And then comes: “Some people say Death’s heart is as dead and black as a piece of coal, but that is not true. Beneath his inky cloak, Death’s heart is as red as the most beautiful sunset and beats with a great love of life.” He tells them a story of Sorrow and Grief meeting and falling in love with Delight and Joy. “What would life be worth if there were no death? Who would enjoy the sun if it never rained? Who would yearn for day if there were no night?”

Jackie: Cry, Heart, But Never Break comes to us from Denmark. It was written by Glenn Ringtved, illustrated by Charlotte Pardi and translated by Robert Moulthrop (Enchanted Lion Books, 2016). This book also deals with loss. Four children live with their grandmother — “A kindly woman, she had cared for them for many years.” Then Death knocks at the door. The children decide to forestall Death’s mission with coffee. They will keep him drinking coffee all night so he cannot take their grandmother, thus giving her another day of life. Eventually he has had enough. And one of the children asks why grandmother has to die. And then comes: “Some people say Death’s heart is as dead and black as a piece of coal, but that is not true. Beneath his inky cloak, Death’s heart is as red as the most beautiful sunset and beats with a great love of life.” He tells them a story of Sorrow and Grief meeting and falling in love with Delight and Joy. “What would life be worth if there were no death? Who would enjoy the sun if it never rained? Who would yearn for day if there were no night?”

When Death goes to the Grandmother’s room, he says to the children, “Cry, Heart, but never break. Let your tears of grief and sadness begin a new life.” Charlotte Pardi’s illustrations are perfect for this book, simple and tender. We see what appears to be quickly-sketched furniture in the night kitchen — we know this is a story. And yet we connect with the emotions on the children’s faces.

Phyllis: I love that the children ply Death with coffee, which Death loves, strong and black, and that it’s the youngest child who looks right at Death and eventually puts her hand over his. But even coffee can’t stop Death; when he goes upstairs the children hear the window open and Death say, “Fly, soul, fly away.” Their hearts grieve and cry but do not break. Some (but not all) of the best books about Death come, interestingly, from other countries. But this book is not only about Death it is about the necessity of a life with both sorrow and grief and also joy and delight. This is a book that makes me cry and hope for all our hearts that they never completely break.

Jackie: We started with connection — the connections of babies and families, and we have come round to loss of connection, when what remains is love. Our hearts will hold us up.

What a beautiful post. Thanks so much for your heart-felt stories of books with heart.