We feel called this month to celebrate the many accomplishments of Black women in this country — some of whom are historical icons, too many of whom we have we have never heard of. Courage, persistence, resourcefulness describe all of these women: survival qualities we all need to call on in these times.

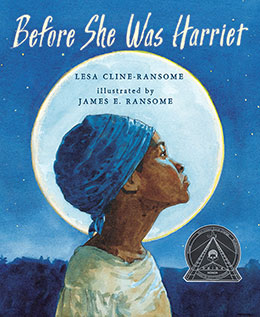

Harriet Tubman is one of the black historical figures that many schoolchildren and adults know about for her work in leading slaves to freedom. In Before She Was Harriet by Lesa Cline-Ransome, illustrated by James Ransome’s beautiful full-bleed paintings in rich, deep colors, we learn so much more about the life of this brave and determined woman.

Harriet Tubman is one of the black historical figures that many schoolchildren and adults know about for her work in leading slaves to freedom. In Before She Was Harriet by Lesa Cline-Ransome, illustrated by James Ransome’s beautiful full-bleed paintings in rich, deep colors, we learn so much more about the life of this brave and determined woman.

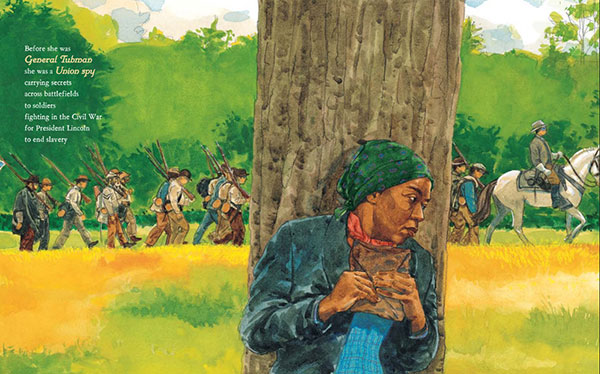

In spare and lyrical prose, Ransome tells Harriet Tubman’s life backward, beginning from when she was an old woman, “tired and worn, her legs stiff, her back achy.”

But before she was an old woman, Harriet was a suffragette, fighting for women’s right to vote, “her voice rising against injustice.” Before she was a suffragette, she was General Tubman, helping enslaved people to escape during the Civil War and spying for the union. Before that Harriet was a nurse, “caring for those hit by bullets and hatred and fear … in the bloodied dirt of southern soil.”

written by Lesa Cline-Ransome, Holiday House

Before that, she was Aunt Harriet, who helped her parents flee slavery, and she was Moses, a conductor on the underground railroad, “with no trains, no tracks, just passengers traveling to freedom.” Ransome takes us back to when Harriet was a child named Araminta, called Minty, taught by her father to read the woods and the stars, yet enslaved by people who broke her back but not her spirit. When she married a free black man in 1844, she renamed herself Harriet.

This “wisp of a woman with the courage of a lion” lived a full and determined life. Through it all she “dreamed of living long enough to one day be old and stiff and wrinkled, tired and worn and free.”

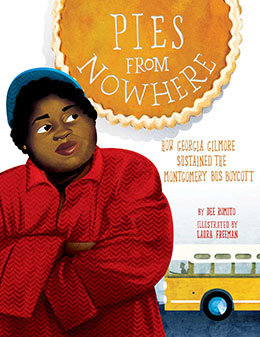

While Before She Was Harriet begins with Harriet as an old woman, Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore Sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Dee Romito, illustrated in strong colors by Laura Freeman, begins with Georgia Gilmore as a young girl and moves quickly forward from her childhood on a farm in Alabama. When Georgia grew up she worked as a cook at the National Lunch Company in segregated Montgomery, the city where, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat for a white passenger, beginning the Montgomery bus boycott. Black people, about 75% of the ridership, organized to not ride the buses at all. Georgia had already quit riding the buses because of how badly drivers had treated her, once demanding she get off the front of the bus after paying her fare and re-enter through the rear door, then driving away before she could re-board the bus.

While Before She Was Harriet begins with Harriet as an old woman, Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore Sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Dee Romito, illustrated in strong colors by Laura Freeman, begins with Georgia Gilmore as a young girl and moves quickly forward from her childhood on a farm in Alabama. When Georgia grew up she worked as a cook at the National Lunch Company in segregated Montgomery, the city where, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat for a white passenger, beginning the Montgomery bus boycott. Black people, about 75% of the ridership, organized to not ride the buses at all. Georgia had already quit riding the buses because of how badly drivers had treated her, once demanding she get off the front of the bus after paying her fare and re-enter through the rear door, then driving away before she could re-board the bus.

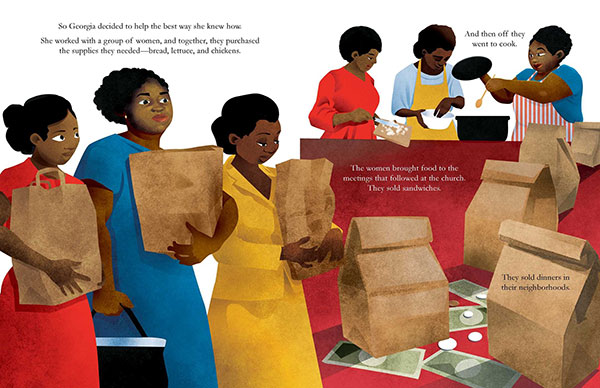

Georgia wanted to help support the boycott, and what she knew best was cooking, so she and a group of other women bought groceries and cooked meals for meetings and boycotters. They sold sandwiches, dinners, and desserts — sweet potato pie, peach pie, red velvet cake, 7‑up cake — in their neighborhoods. They gave the money from these pies and cakes to the boycott to buy gas and even stations wagons to transport the boycotters. But the women had to work in secret for fear of losing their jobs, so whenever Georgia was asked where the money they donated came from, she would answer, “Nowhere.”

After Georgia was called to testify in court about how she had been mistreated by a bus driver, the National Lunch company fired her. With the help and encouragement of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Georgia began feeding folks out of her home and delivering meals of fried chicken, black eyed peas with okra, fresh corn muffins, apple pie, even homemade macaroni and cheese to earn money to support her family.

On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court declared that Montgomery’s segregated buses were unconstitutional. People could sit anywhere they wanted on buses. Georgia celebrated with folks, but she knew, too, that there were still plenty of fights ahead.

And so she kept right on cooking.

This book will make readers hungry for sweet potato pie and mac and cheese, but even more, it will make readers hungry for justice. It includes a list of sources and an author’s note which ends with a quote from Georgia:

“You cannot be afraid if you want to accomplish anything. You got to have the willing, the spirit, and above all, you got to have the get-up.”

Fighting injustice takes many forms, from cooking “pies from nowhere” to leading slaves to freedom to voting, protesting, and never giving up the fight. Harriet Tubman and Georgia Gilmore had the get-up to fight for justice. We can, too.

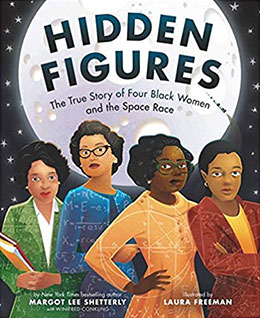

And we can be inspired by women who would not be trapped by the way things were. They pushed to expand the possible. Hidden Figures written by Margot Lee Shetterly and illustrated by Laura Freeman is the true story of four amazing African American mathematicians who made many of the early NASA missions possible — Dorothy Vaughn, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, Christine Darden. Why didn’t we hear of them for so many decades?

And we can be inspired by women who would not be trapped by the way things were. They pushed to expand the possible. Hidden Figures written by Margot Lee Shetterly and illustrated by Laura Freeman is the true story of four amazing African American mathematicians who made many of the early NASA missions possible — Dorothy Vaughn, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, Christine Darden. Why didn’t we hear of them for so many decades?

The book gives brief biographies of the four women and reminds readers that when they began their careers “computers were actual people” who were very good at math.

Each of the four always knew she was good at math but faced many hurdles to get to do this job they loved: they were women (most engineers were men); they were not white (most people working on the early space projects were white).

When they started their careers, these women could not work in the same rooms as the white mathematicians, use the same bathrooms, eat at the same tables. But they could do math. They sure could do math.

Dorothy Vaughn wanted to serve her country during WWII and applied for a position at National Advisory Commission for Aeronautics and was hired as a computer. She stayed on with the Commission after the war to continue the effort to design safer, faster planes.

In 1952 Mary Jackson got a job as a computer at Langley Air Force Base. Mary’s real goal was to become an engineer. No one encouraged her. “She wasn’t allowed to go inside the white school where the [engineering] classers were taught…. She refused to give up. She got permission to enter the school building and take the math classes and she earned good grades. Because she didn’t give up Mary Jackson became the first African American female engineer at the laboratory.”

“Katherine Johnson was good at math and always asked lots of questions. In 1953 she applied to the laboratory for a computer job… and was placed on a team that tested actual planes while they were flying in the air.” She wanted to help write research reports but “women weren’t allowed” to attend the meetings where the reports were prepared. She asked her boss if she could attend these meetings. He said women weren’t allowed. She asked again, and again, and again, until finally the rules were changed. She was the first woman to sign her name to a lab report. Katherine Johnson was so good at math John Glenn wanted her to review the computers’ projections of his landing to be sure it would go as expected.

In the 1960s Jim Crow laws began to change. Black and white mathematicians could eat together, work together, share the same bathrooms. Christine Darden started working at Langley in 1967. She first worked on the project to put astronauts on the moon. The four women and the other NASA engineers achieved success on July 20, 1969, when the Apollo spacecraft touched down on the moon.

A timeline at the end of the book places these remarkable women’s lives in the context of other important dates in space exploration.

This is a wonderful introduction to a piece of history that we all should know. Our favorite illustration in the book is a spread toward the end which recounts civil rights progress. We see people of all races sitting together on a subway. Outside the windows of the subway we see the faces of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and other civil rights heroes. We need the power of their spirits, who have guided us over the decades, and the perseverance of these women as much as ever. Let us be inspired by them and moved to action to make a world where all can use their gifts.

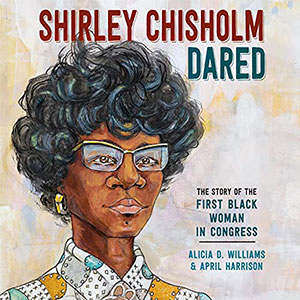

One Black leader who was not hidden in her time was Shirley Chisolm. We learn her story in Alicia D. Williams’ lively picture book biography Shirley Chisolm Dared The Story of the First Black Woman in Congress, illustrated by April Harrison (Random House, 2021). This story begins when precocious three-year-old Shirley St. Hill goes, with her two sisters, from Brooklyn to live with her grandmother in Barbados. After six years she returns to Brooklyn, still precocious.

One Black leader who was not hidden in her time was Shirley Chisolm. We learn her story in Alicia D. Williams’ lively picture book biography Shirley Chisolm Dared The Story of the First Black Woman in Congress, illustrated by April Harrison (Random House, 2021). This story begins when precocious three-year-old Shirley St. Hill goes, with her two sisters, from Brooklyn to live with her grandmother in Barbados. After six years she returns to Brooklyn, still precocious.

After graduating from Brooklyn College, she gets a job as a teacher’s aide in a nursery school and takes courses after work at Columbia Teachers College. Soon she is holding down administrative positions.

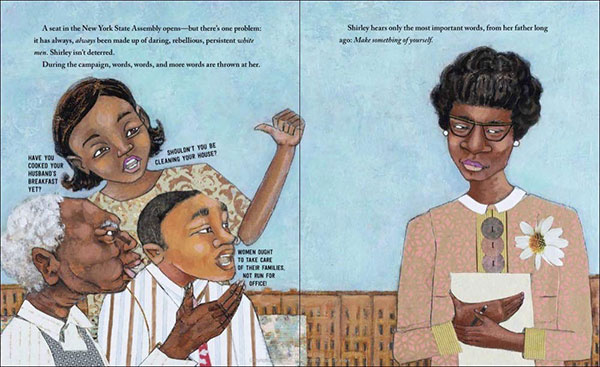

All her life her father has told her, “Make something of yourself.” And she sees work to be done. In her neighborhood of Bedford Stuyvesant there is a housing shortage, garbage pick-up is spotty, kids need day care and preschool. She asks questions — why can’t we have more? She joins a club of Democrats — and is assigned to decorate cigar boxes! She asks why women only get to write cards and decorate boxes. Eventually she is asked to leave.

Unbothered, she continues to ask why her neighborhood is so ignored. Then, “Shirley steps her white oxford heels back into politics” and runs for a seat in the New York State Assembly, a seat that had always been held by a white man. She wins!

After three years in the New York State Assembly Shirley Chisolm decides to run for Congress. “Her fellow assemblymen refuse to support her. Even reporters ignore her, only interviewing her opponent.” But she campaigns tirelessly – talking to people in their living rooms, at meetings, on the street. Fifty-two thousand four hundred and thirty three votes were cast in that election. Shirley Chisolm won by twenty one thousand votes.

Williams’s biography ends with this victory, but a page of back matter gives readers the whole outline of Shirley Chisholm’s remarkable life.

Williams’s language perfectly matches Chisholm’s lively, spunky spirit. And the illustrations, too, are lively and engaging. This is a book readers will go back to again and again — for inspiration and for joy.

Bibliography

Cline-Ransome, Lesa. Before She Was Harriet. (illus. by James E. Ransome). Holiday House, 2017.

Romito, Dee. Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore Sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott. (illus. by Laura Freeman). little bee books, 2018.

Shetterly, Margot Lee. Hidden Figures: The True Story of Four Black Women and the Space Race. (illus. by Laura Freeman.) HarperCollins, 2018.

Williams, Alicia D. Shirley Chisholm Dared: The Story of the First Black Woman in Congress. (illus. by April Harrison). Anne Schwartz Books, 2021.

Related Books

Helaine Beeker. Counting on Katherine. (illus. by Dow Phumiruk). Henry Holt, 2018.

Slade, Suzanne. A Computer Called Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Helped Put a Man on the Moon. (illus. by Veronica Miller Jamison ) Little Brown, 2019.

Thorpe, Andrea. The Story of Katherine Johnson. Rockridge Press, 2021.

Brown, Katheryn Russell. She Was the First. (illus by Eri Velasquez). Lee & Low, 2020.

Chambers, Veronica. Shirley Chisholm is a Verb (illus. by Rachelle Baker) Dial, 2020.