How to Get Your Children’s Book Published

Step #6: Writing Story

Hello again, Educators! For those of you who want to publish a children’s book, it’s time to talk about story (otherwise known as narrative). Of course there are also expository children’s books (like The Great Lakes!); but the majority of children’s books tend to have some sort of narrative structure.

If you’ve read my previous articles in Bookology, you may be wondering: Why did it take you so long to address the actual writing of a story? Because audience is key. Obviously, you are writing for children but, to publish a book, you are also writing for an editor in the children’s book industry. The first five articles in this series hopefully explained who that is and how you as an author fit into the process.

Story is ever-present in daily speech, movies, TV, social media, and books; we all know it when we see or hear it — until we try to write one. Early on, I had the eye-opening experience of drafting a few early picture books and having people in critique groups say that my manuscripts “had no real story” at all. Turns out that story is more than a bunch of artful words that start, go on, and end.

STORY STRUCTURE

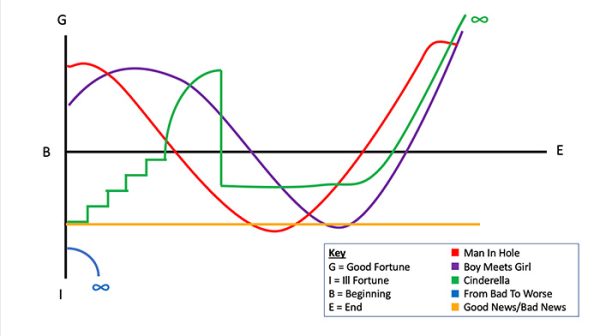

Many educators already know a lot about story from teaching it; but there are thousands of additional sources about narrative structure. Some recommendations for children’s writers include: Lisa Cron’s Story Genius, Martha Alderson’s The Plot Whisperer, Ann Whitford Paul’s Writing Picture Books and Kurt Vonnegut’s classic story plot maps found everywhere, including here. As you read about the fascinating topic of story structure, it can grow complex and overwhelming.

THREE KEY ELEMENTS

As you read about the fascinating topic of story structure, it can grow complex and overwhelming. For me, simplest is best. I think of a story as having three key elements:

- Action — characters must do things

- Conflict — characters must have a challenge, they must ‘fight’ things.

- Resolution/Change — the character/situation changes and the story’s ending is logical based on what has come before.

The story structure map that I use most often to help me find the narrative structure for my picture books is called The Story Spine/Pixar’s Story Structure found at this link, and in many other online forums. I’ll cover mapping a bit more next time.

AN AUTHOR’S OBLIGATION TO READERS

Children’s author Alice B. McGinty also taught me to about an author’s obligations to readers. When creating a story, Alice says that authors must:

- Grab the reader with a compelling character who wants or needs something important.

- Keep the reader’s attention as struggles and obstacles are faced.

- Satisfy the reader with a resolution.

I find Alice’s model useful because it forces me out of my head and into my young readers’ heads from the start. It doesn’t matter if we like the idea or first draft of our books if young readers will not. For example, the first lines of the first draft of what became my first picture book, Fearless, were: “No jobs. No money. No hope. Things were pretty tough in Barnesville, Georgia that summer.” What’s wrong with those lines? Nothing! In fact, I still like them … EXCEPT that the young kids in my reading audience don’t have jobs, they typically don’t spend much time thinking about money, and hope is something a children’s book needs to provide! Those lines spoke to me, and they might work for older readers, but they do not relate to an audience of picture book age children.

Alice’s model puts readers (in this case: kids) first. And you should too, at every step of the story-writing process. What will young readers find fascinating? What situations will they relate to? What background knowledge do they need? Another example: I recently read a new writer’s picture book draft which described the setting’s times using the phrase “World War II.” The problem with that reference, and most dates in children’s literature, is that they mean absolutely nothing to an 8‑year-old (or an 11-year-old, or think about it, what does a year like “1915” even mean to you as an adult?) Children’s writers should never talk down to their audience, but we also can’t talk past them! We must live in their heads, figure out what they already know and what they need to know, what they already feel and what they need to feel for our story to make sense to them intellectually and emotionally.

COMMON PITFALLS

Over the years, I have worked with adults as picture book students and read hundreds of their picture book drafts. Many new writers’ picture books have common pitfalls. Three to watch out for are dated ideas, stereotypes, and/or preaching. For example, a story might seem dated if it contains rigid gender role assumptions or stilted dialogue or sounds like children’s literature from 40 years ago. Other manuscripts contain stereotypical characterizations of certain people, cultures, or communities. This can happen when authors write about communities or cultures not their own. I hope you find this startling list of stereotypes in children’s books from the San Francisco Library helpful. And though some recent children’s books still include some kind of moral lessons (be kind, be brave, be yourself, etc.) today’s editors look for it to grow from the uniqueness of the story itself rather than the author “preaching” or “instructing” the reader about (for example) “ways to welcome your baby sister.”

However, by FAR, the most common pitfall I see in picture book drafts is no real story at all! After setting up decent characters and a fine setting, many new authors have their characters meander through the manuscript spending large portions of time thinking, and not enough time doing anything.

Stories for children MUST:

- Have a challenge/problem/issue that is actionable by the characters.

- That action steadily builds until it “pays off” in a resolution.

- That solution must come from the main (kid) character (or a character “standing in” for the child, like a puppy, squirrel, tree, or a rock.) Adults don’t solve the conflict or problem, the “kid” does. No adult (or other random) saviors!

- The end/resolution make sense in the context of the story’s framework or “set up.” Beginnings create middles, endings circle back to beginnings.

These pitfalls cover picture books stories that do not work, but to expand my own knowledge, I asked a few editors if there are common “flaws” or pitfalls in the middle grade or YA novels or narrative nonfiction that they pass up. Here were their answers, surprisingly like those I’ve noticed in picture books:

- the plot, characters, setting/context is not logical or developed

- the voice or tone is generic or boring, anyone could have written it

- the dialogue is stilted or dated

- the manuscript is not marketable — similar to what’s already published or not kid-friendly

- the writing has too much explanation not enough action.

It is editors like these who will decide whether to publish your writing, so your job is to hunt through your existing draft for these issues before you send it off for their consideration. How to do that? You revise! Revision tips and tricks is the topic for the next article in this series. Until then, keep your writing chair warm and keep working on your writing goals. A little work each day can produce amazing results.

More from this series …

Before, Step #5, The Book Process