For centuries, humans have explored the potential of flight. Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks from the late 1480s to the mid-1490s include several designs of wing mechanisms and flying machines.1 None of the designs achieved its goal, and it would be almost 300 years before humans took to the air, not with wings or machines but in hot-air balloons. Advances in air travel have continued, and its allure has never waned. Four Caldecott Award books celebrate the exhilaration of flight, with two journeys inspired by history and two by imagination.

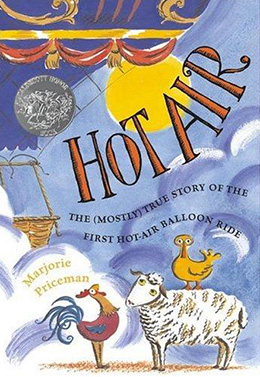

For Hot Air: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Hot-Air Balloon Ride, author-illustrator Marjorie Priceman’s cover art prepares readers for the rollicking ride ahead: the commanding hand-lettered, double-entendre title; a subtitle that rolls across the image; and three pensive farm animals about to steal the show. The story opens at the palace of Versailles in France with a witty, though accurate, account of the first successful flight of a hot-air balloon on 19 September 1783. At the demonstration are inventors Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier, the French king and queen, numerous dignitaries, and the balloon’s passengers: the duck, sheep, and rooster featured on the cover. Once aloft, the “(mostly) true story” begins.

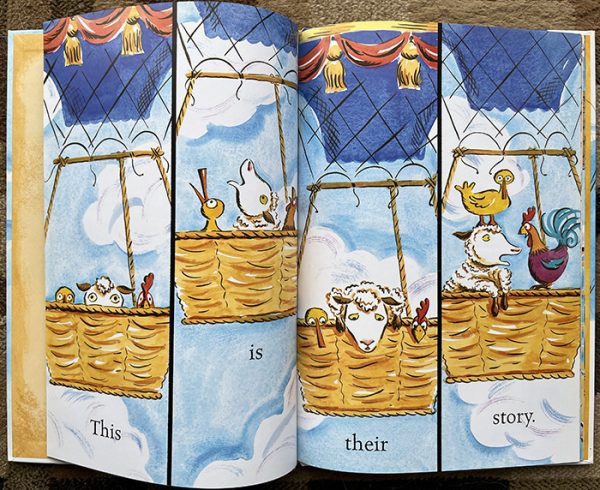

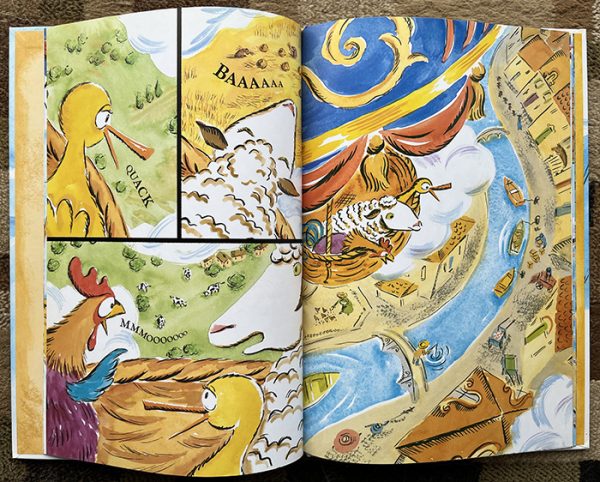

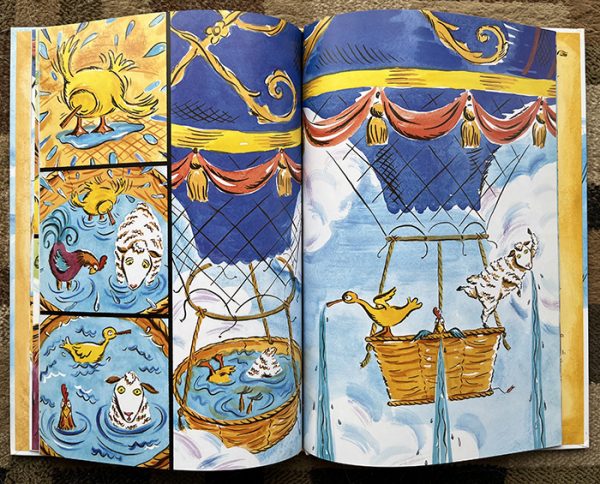

In a nearly wordless sequence, the animals encounter several calamities, including drying laundry, a boy’s arrow, a dangerous spire, angry birds, and spouting fountain water. Ever-changing page designs drive the story forward. Among the full-bleed single- and double-page spreads, Priceman incorporates two or four panels on some pages. Blue and gold hues, highlighted by reds and greens, dominate the colorful spreads. Long views are interspersed with close-ups, along with a few dizzying vistas looking downward from the balloon’s basket. The “artistic gaiety” of Priceman’s art is “reminiscent of earlier styles” of book illustration.2 Expressionistic gouache and india ink3 artwork conveys verve and energy. The animals’ cartoon eyes reveal much expression, from confusion to terror to glee.

of the First Hot-Air Balloon Ride, published by Anne Schwartz / Atheneum, 2005

of the First Hot-Air Balloon Ride, published by Anne Schwartz / Atheneum, 2005

of the First Hot-Air Balloon Ride, published by Anne Schwartz / Atheneum, 2005

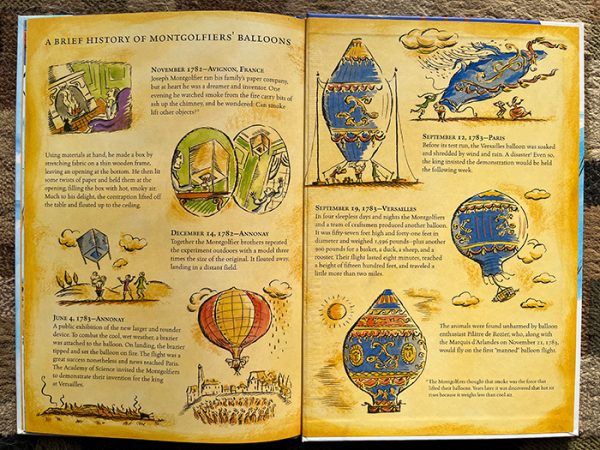

Priceman concludes her 2006 Caldecott Honor book by reassuring readers that, in fact, the farmyard passengers were truly found unharmed after the eight-minute, two-mile flight. Back at the palace, “they are greeted with flowers, song, and better food than usual.” On a more serious note, the author-illustrator includes “A Brief History of Montgolfiers’ Balloons” on the back endpapers. Text and small illustrations describe the brothers’ curiosity about smoke and their experiments sending contraptions afloat, beginning with small objects in November 1782 and ending with the remarkable balloon flight at Versailles.

Hot-air balloons and, later, hydrogen-filled airships drifted to the sidelines of aviation history upon the invention of and experimentation with gliders and airplanes in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Orville and Wilbur Wright’s groundbreaking twelve-second flight of a human-carrying engine-powered plane near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on 17 December 1903 spurred others around the world to improve their planes and accomplish new feats. One of those enthusiasts was the determined Louis Blériot of Cambrai, France, the subject of Alice and Martin Provensen’s 1984 Caldecott Medal book The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel with Louis Blériot.

Hot-air balloons and, later, hydrogen-filled airships drifted to the sidelines of aviation history upon the invention of and experimentation with gliders and airplanes in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Orville and Wilbur Wright’s groundbreaking twelve-second flight of a human-carrying engine-powered plane near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on 17 December 1903 spurred others around the world to improve their planes and accomplish new feats. One of those enthusiasts was the determined Louis Blériot of Cambrai, France, the subject of Alice and Martin Provensen’s 1984 Caldecott Medal book The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel with Louis Blériot.

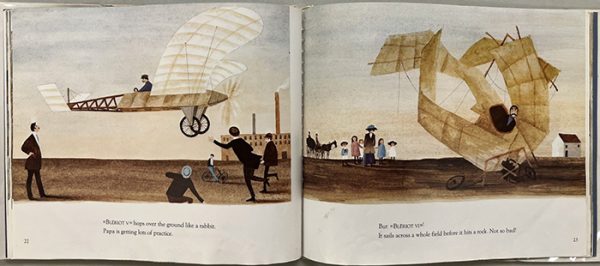

As the story opens in 1901, readers meet Blériot, an inventor of automobile accessories, and his wife and five children seated formally at the dining room table. Later, when the family witnesses a dirigible flying above the city, Papa Blériot is so captivated that he devotes his efforts to creating a flying machine, the first of which he tests a few years later. Its failure leads to another design, then several more, each plane shown in action or post-crash in sepia-toned acrylic and pen and ink4 paintings with the Provensens’ “flat, decorative modern technique”5 in an almost naïf style. The artistic team infuses humor into most of the full-bleed single‑, three-quarter‑, and double-page spreads, especially with Blériot’s less successful exploits. Perspectives shift throughout the book to capture different vantage points from land or sky. Readers see the passage of time through the ever-present children, always properly dressed, who grow and mature through the book.

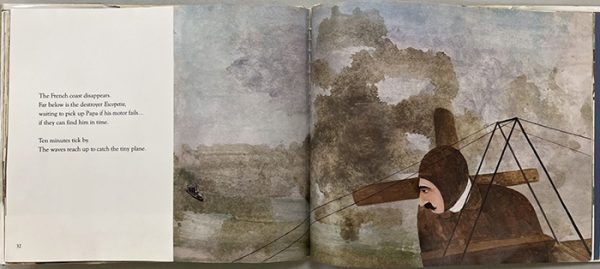

The lighthearted tenor of the story takes a turn when Blériot sets out to be the first person to fly 20 miles across the English Channel. The year is 1909, and he is ready to put his Blériot XI craft to the test. The next four spreads focus on the aviator en route from Calais, France, to Dover, England. Here, grey tones cast a somber mood as he flies solo and, at times, loses sight of water in the thick fog. When the sky lightens, the green English countryside welcomes the pilot as he approaches Dover and a crowd of well-wishers. Despite an awkward landing, Louis Blériot triumphs, landing 37 minutes after departure on this “glorious flight.”

The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel with Louis Blériot, Viking, 1983

The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel with Louis Blériot, Viking, 1983

Author-illustrators Alice and Martin Provensen met in 1943 while working as animators at Walter Lantz Studio in Los Angeles. The collaborative nature of animation work prepared them to transition to co-creating picture books in 1947. Describing their process, Alice explains, “We work together on all our illustrations, much as the medieval scribes and scriveners did, passing the drawings back and forth between us, adding this or taking out that, until each is satisfied.”6 For Glorious Flight, she adds, “We both worked on most of the drawings and paintings, sometimes with one of us doing the background and the other doing the costumes and figures.”7 From this collaboration, the Provensens created a glorious tribute to Louis Blériot.

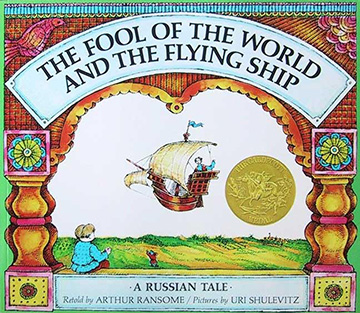

Long before air travel became a reality, flying ships captured imaginations, from conceptual etchings in 16978 and 17859 to folk stories. One such tale was collected and retold by English writer Arthur Ransome. In 1913, Ransome traveled to Russia, where he taught himself the language and researched traditional folktales. Ransome published Old Peter’s Russian Tales in 1916, not as a scholarly folklorist, instead “taking my own way with them more or less, writing them mostly from memory.”10 Many years later, artist Uri Shulevitz found inspiration in the protagonist of “The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship,” illustrating the tale in playful pen and brush with black and colored inks11 in his 1969 Caldecott Medal-winning book of the same name.

Long before air travel became a reality, flying ships captured imaginations, from conceptual etchings in 16978 and 17859 to folk stories. One such tale was collected and retold by English writer Arthur Ransome. In 1913, Ransome traveled to Russia, where he taught himself the language and researched traditional folktales. Ransome published Old Peter’s Russian Tales in 1916, not as a scholarly folklorist, instead “taking my own way with them more or less, writing them mostly from memory.”10 Many years later, artist Uri Shulevitz found inspiration in the protagonist of “The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship,” illustrating the tale in playful pen and brush with black and colored inks11 in his 1969 Caldecott Medal-winning book of the same name.

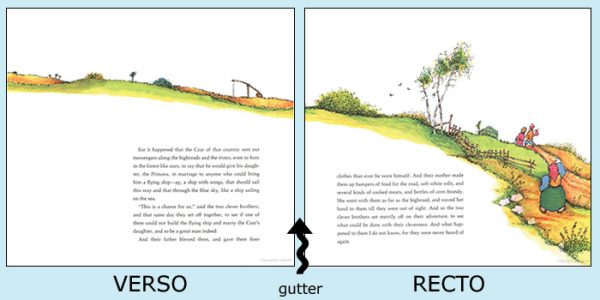

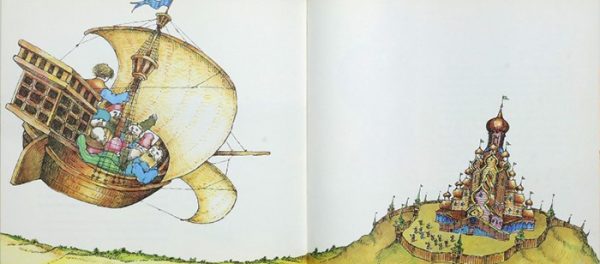

Shulevitz’s mastery of page design shines throughout the book. The long story is broken down into pithy paragraphs while full-bleed illustrations work around the text in imaginative ways, with dominant images extending beyond the gutter from the verso or the recto, horizontal illustrations extending across the top half of the spread, and diagonal or curved artwork moving across a page. Two wordless double-page spreads appear at turning points in the story: the initial launch of the flying ship with the Fool alone over a vast colorful landscape and the descent of the flying ship and its joyful passengers as it approaches the Czar’s impressive palace. Shulevitz values white space as “empty areas for the eye to rest”12 and incorporates it judiciously throughout the book.

Shulevitz’s mastery of page design shines throughout the book. The long story is broken down into pithy paragraphs while full-bleed illustrations work around the text in imaginative ways, with dominant images extending beyond the gutter from the verso or the recto, horizontal illustrations extending across the top half of the spread, and diagonal or curved artwork moving across a page. Two wordless double-page spreads appear at turning points in the story: the initial launch of the flying ship with the Fool alone over a vast colorful landscape and the descent of the flying ship and its joyful passengers as it approaches the Czar’s impressive palace. Shulevitz values white space as “empty areas for the eye to rest”12 and incorporates it judiciously throughout the book.

The cartoon style and off-kilter perspectives complement the exaggerated characters and fantastic situations. The palette of primary colors, greens, and earth tones befit both the rural scenes and those at the palace, breathing life into the folktale. Shulevitz succeeds in his effort to introduce this story to a younger audience, honoring the Fool, an unlikely hero who “refuses to be bound by the generally accepted opinion of himself … [and] welcomes the varied companions who eventually help him in his task.”13

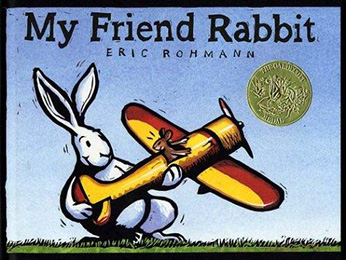

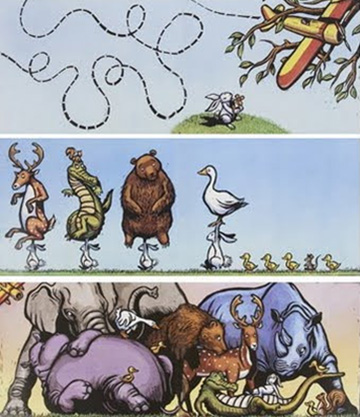

The unlikely hero of My Friend Rabbit is the perpetrator of a great mishap, which he attempts to rectify with aplomb. In author-illustrator Eric Rohmann’s 2003 Caldecott Medal book, Rabbit’s exuberance leads to his launching Mouse’s new airplane into a tree. Undaunted, Rabbit springs into action by enlisting a cast of animal characters to help free the plane. The images that follow flow like scenes in an animated film, with Rabbit pulling, pushing, or carrying one animal at a time, many ridiculously bulky and awkward, to an unknown destination. The story reaches the climax when readers catch up to a teetering tower of animals just before it collapses.

The unlikely hero of My Friend Rabbit is the perpetrator of a great mishap, which he attempts to rectify with aplomb. In author-illustrator Eric Rohmann’s 2003 Caldecott Medal book, Rabbit’s exuberance leads to his launching Mouse’s new airplane into a tree. Undaunted, Rabbit springs into action by enlisting a cast of animal characters to help free the plane. The images that follow flow like scenes in an animated film, with Rabbit pulling, pushing, or carrying one animal at a time, many ridiculously bulky and awkward, to an unknown destination. The story reaches the climax when readers catch up to a teetering tower of animals just before it collapses.

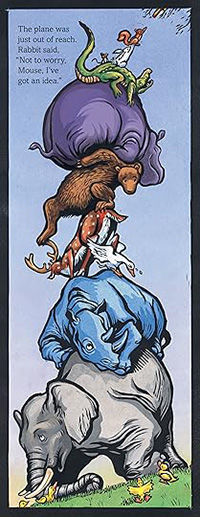

Bold lines dominate the artwork, mirroring Rabbit’s resolve. Carved from a linoleum-like material and hand-colored with watercolors,14 the “active and chunky and energetic”15 relief prints convey movement. On most spreads, textured grass in horizontal or slightly diagonal lines not only create a sense of stability but move readers’ eyes across the long framed spreads. Broken curved lines trailing the airplane suggest its precarious flight. Implied diagonal lines, such as when the smallest animals strain to reach the plane or when the heap of animals glares at Rabbit, exude energy and tension. The book’s most noteworthy vertical line, the unsteady stack of creatures, is so dramatic that the orientation of the book turns to its edge, slowing the story momentarily to “[make] the reader look more closely.”16

Rohmann is an astute visual storyteller. With just a few remarks by Mouse during the story, the narrative is driven by the humorous artwork. In a cartoon style, he carves creatures great and small in various states of emotion, from enthusiastic or bewildered to reluctant or angry. Central to the story, the red and yellow plane is in contrast with the primary palette of cool and neutral hues, while the background colors change subtly as the drama increases.

The sequential nature of the story reflects Rohmann’s passion for comic books as a boy. “Comics always awakened my imagination, drew me into the stories, and suggested further adventures.”17 Indeed, the author-illustrator suggests that further adventures await Mouse and Rabbit on the final page when the two friends find themselves in a new predicament with the cherished plane. Rabbit repeats with dubious conviction, “Not to worry, Mouse, I’ve got an idea.”

illustration of animal friends © Eric Rohmann from My Friend Rabbit, published by Roaring Brook Press, 2002

Taking readers aloft, these Caldecott Award books share similarities, all told with a touch of humor and featuring heroes that beat the odds. While the artistic styles of the illustrations are wildly different, the picture books entice readers with images that set the mood and propel the narrative, taking readers onward and upward to discover new challenges.

Books Cited

Priceman, Marjorie. Hot Air: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Hot-Air Balloon Ride. New York: Anne Schwartz/Atheneum, 2005.

Provensen, Alice, and Martin Provensen. The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel with Louis Blériot. New York: Viking, 1983.

Ransome, Arthur. The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship: A Russian Tale. Illustrated by Uri Shulevitz. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1968.

Ransome, Arthur. Old Peter’s Russian Tales. Rev. ed. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1971.

Rohmann, Eric. My Friend Rabbit. Brookfield, CT: Roaring Brook Press, 2002.

Notes

- Christopher James Botham, “Leonardo da Vinci and Human Flight,” On Verticality, On Verticality, 8 April 2020.

- Deborah Stevenson, “Marjorie Priceman,” Rising Star, The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books Online, 1 July 1999.

- Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), The Newbery & Caldecott Awards: A Guide to the Medal and Honor Books (Chicago: American Library Association, 2020), 110.

- ALSC, Newbery & Caldecott Awards, 129.

- George James, “Martin Provensen, Illustrator, Specialist in Children’s Books,” New York Times, 30 March 1987, Late Edition (East Coast).

- Shannon Maughan, “Obituary: Alice Provensen,” Publishers Weekly Online, PWxyz, LLC, 1 May 2018.

- Leonard S. Marcus, “Alice Provensen and Martin Provensen,” in Side by Side: Five Favorite Picture-Book Teams Go to Work (New York: Walker & Company, 2001), 24.

- Christopher James Botham, “Francesco Lana de Terzi’s Aerial Ship,” On Verticality, On Verticality, 31 March 2020.

- “The Flying Ship,” Show Me, Culture24, 6 October 2021.

- Arthur Ransome, “Note,” in Old Peter’s Russian Tales, rev. ed. (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1971).

- ALSC, Newbery & Caldecott Awards, 141.

- Julie Cummins, “Talking with Uri Shulevitz.” Book Links 17, no. 1 (September 1, 2007): 25.

- Newbery and Caldecott Medal Books 1966 – 1975, ed. Lee Kingman (Boston: Horn Book, 1975), 208.

- ALSC, Newbery & Caldecott Awards, 113.

- “Profile: Eric Rohmann:Transcript,” Reading Rockets, WETA, 2025.

- Vicki Arkoff and Stephanie Gwyn Brown, “My Friend Eric Rohmann: Q&A with the 2003 Caldecott Medal Winner for Illustration,” Kite Tales, SCBWI Tri-Regions of Southern California, 16 March 2004.

- Eric Rohmann, “Caldecott Medal Acceptance,” Horn Book Magazine 79, no. 4 (July 1, 2003): 395.

Bibliography

Arkoff, Vicki, and Stephanie Gwyn Brown. “My Friend Eric Rohmann: Q&A with the 2003 Caldecott Medal Winner for Illustration.” Kite Tales. SCBWI Tri-Regions of Southern California, 16 March 2004.

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). The Newbery & Caldecott Awards: A Guide to the Medal and Honor Books. Chicago: American Library Association, 2020.

Botham, Christopher James. “Francesco Lana de Terzi’s Aerial Ship.” On Verticality. On Verticality, 31 March 2020.

Botham, Christopher James. “Leonardo da Vinci and Human Flight.” On Verticality. On Verticality, 8 April 2020.

Cummins, Julie. “Talking with Uri Shulevitz.” Book Links 17, no. 1 (September 1, 2007): 23 – 25.

James, George. “Martin Provensen, Illustrator, Specialist in Children’s Books,” New York Times, 30 March 1987, Late Edition (East Coast).