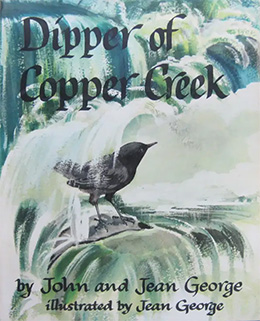

Sometimes children find a book that they love beyond all reason. They check it out of the library again and again. If asked, they can’t answer why that particular book speaks to them. It just does. I was that way with Dipper of Copper Creek, written by John L. George, illustrated by Jean George, published in 1956. It was about a bird that lives under waterfalls in Colorado and a boy who raised one by hand. I was captivated by water ouzels. The Georges’ animal biographies were always told from the creature’s authoritative point of view in prose that sparkled:

Sometimes children find a book that they love beyond all reason. They check it out of the library again and again. If asked, they can’t answer why that particular book speaks to them. It just does. I was that way with Dipper of Copper Creek, written by John L. George, illustrated by Jean George, published in 1956. It was about a bird that lives under waterfalls in Colorado and a boy who raised one by hand. I was captivated by water ouzels. The Georges’ animal biographies were always told from the creature’s authoritative point of view in prose that sparkled:

[The water ouzel] dipped and dipped, sang, plunged into the roiling foam of the falls. He rode to the bottom on a swirl, grasped a minute crack in a boulder with his toes and listened to the noisy floor of the stream. Rocks hitting rocks, stones being ground into sand, pools being dug, canyon walls being slowly undermined.

The sun penetrated into the depths of the stream, for the water was like glass. He poked around the rock until he found some small crustaceans to eat, then he pumped his wings and bounced to the surface.

If at ten, I had known that Jean George wrote that book, along with more than 100 other nature-based children’s books, I would have been surprised. If I had known that Jean shared her life with 173 wild animal pets, I would have run away to live with her. Other George books gave me a window into the lives of minks, skunks, and owls, and made me long for a wild animal pet. Once, I found a mouse that had fallen into an empty cider jug in our basement. I ran to my mother with the jug, thrilled to have my own pet. I would make tiny clothes for it. My mother took one look at the mouse pawing against the glass and ordered me to let it go, far, far outdoors.

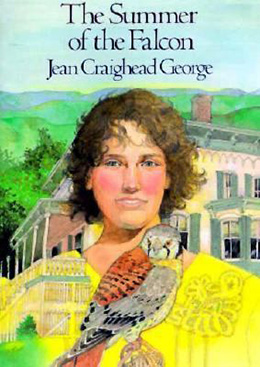

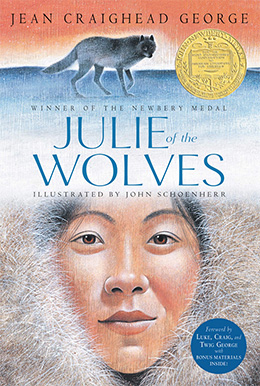

Many of us know of the Newbery-winning author Jean Craighead George. Before Julie of the Wolves, Jean Craighead was born in 1919 and raised in Pennsylvania. Her father was an entomologist. In the summers, Jean, her parents, and her older twin brothers camped in the woods to live off the land. Jean’s first wildlife pet was a baby turkey vulture she named Nod. Her brothers, who introduced the sport of falconry in the U.S. as high school students, gave 13-year-old Jean a kestrel to train. She wrote about that experience in The Summer of the Falcon.

Many of us know of the Newbery-winning author Jean Craighead George. Before Julie of the Wolves, Jean Craighead was born in 1919 and raised in Pennsylvania. Her father was an entomologist. In the summers, Jean, her parents, and her older twin brothers camped in the woods to live off the land. Jean’s first wildlife pet was a baby turkey vulture she named Nod. Her brothers, who introduced the sport of falconry in the U.S. as high school students, gave 13-year-old Jean a kestrel to train. She wrote about that experience in The Summer of the Falcon.

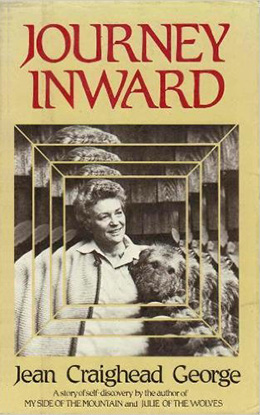

When I discovered Jean’s memoir, Journey Inward (Dutton, 1980), I learned that the men in her family were high achievers. Her brothers became world-renowned experts on grizzly bears. Jean felt “with two such brothers, a younger sister had to be a writer to find her niche.” She began writing stories in third grade. She grew up to work as a reporter for the Washington Post during wartime when she met and married a navy man, John George. “I was ready to marry,” she wrote. “All of me except for that spark in the far right-hand corner that makes each one of us different from everyone else. In that far corner, my own belief in myself as a writer still held out.”

When I discovered Jean’s memoir, Journey Inward (Dutton, 1980), I learned that the men in her family were high achievers. Her brothers became world-renowned experts on grizzly bears. Jean felt “with two such brothers, a younger sister had to be a writer to find her niche.” She began writing stories in third grade. She grew up to work as a reporter for the Washington Post during wartime when she met and married a navy man, John George. “I was ready to marry,” she wrote. “All of me except for that spark in the far right-hand corner that makes each one of us different from everyone else. In that far corner, my own belief in myself as a writer still held out.”

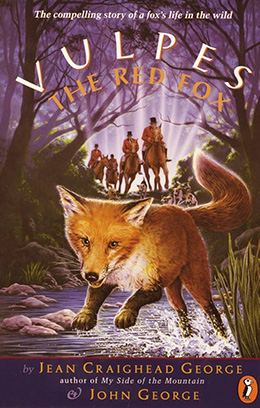

Their first children’s book, Vulpes, the Red Fox, came about when the couple lived in Maryland and learned about foxes. The George method for writing about animals was to keep one as a pet. Their fox pup made a den in the fireplace and draped herself around Jean’s shoulders as she typed notes. She turned those notes into Vulpes. The book was published with John as author and Jean, the true author, as second-string illustrator. And so began a lopsided collaboration of animal biographies. By then John was an ornithologist and they lived in a tent in Pennsylvania while he researched his PhD. Along with being his assistant, Jean took care of the various boarders: raccoons, crows, a skunk, baby birds, and their own baby girl, Twig.

Their first children’s book, Vulpes, the Red Fox, came about when the couple lived in Maryland and learned about foxes. The George method for writing about animals was to keep one as a pet. Their fox pup made a den in the fireplace and draped herself around Jean’s shoulders as she typed notes. She turned those notes into Vulpes. The book was published with John as author and Jean, the true author, as second-string illustrator. And so began a lopsided collaboration of animal biographies. By then John was an ornithologist and they lived in a tent in Pennsylvania while he researched his PhD. Along with being his assistant, Jean took care of the various boarders: raccoons, crows, a skunk, baby birds, and their own baby girl, Twig.

Jean grew up during an era where wives were expected to support their husbands. Her mother was her father’s research assistant. It was the 1950s, therefore Jean followed John from state to state, idea to idea, job to job. But it was no picnic living in a tent during the winter, encouraging John to work on his thesis while she wrote books under his name. She longed to write a book about a boy who lived alone on a mountain. The main character had to be a boy because, as Jean said, “girls were not free to run away and survive except incognito.”

By then Jean had three children. Her marriage was crumbling. She was afraid that spark in the far right-hand corner, her belief that she was destined to be a writer of her own work, would be extinguished.

By then Jean had three children. Her marriage was crumbling. She was afraid that spark in the far right-hand corner, her belief that she was destined to be a writer of her own work, would be extinguished.

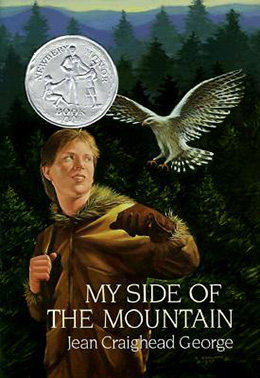

“And so I ran away to the forest to survive — right in my own home. I titled the book My Side of the Mountain, illustrated it and signed it Jean George. When I finished the writing I began another part of the odyssey that was turning out to be me.”

My Side of the Mountain earned a Newbery Honor. Later, Jean wrote two companion books.

Living as a single mother was freeing but not easy. She took on freelance work to support herself and her children. Books and articles flew from her typewriter. With her children bringing home frogs, crows, robins, snakes, owls, tarantulas, ducklings, fish, moths, turtles, bats, and more, she never lacked for subjects. When her children left the nest, she struck off on solo adventures — to Alaska to study wolves, to the American West to learn about bison and sandhill cranes, to the Everglades to experience alligators, orchids, and the ecology of the “river of grass.”

Jean died at the age of 92 in 2012. When working on this article, I scoured my extensive children’s literature library for articles or essays by or about Jean. I found none. After her Newbery in 1973, it seems she fell off the radar. Before Julie of the Wolves was published, she’d already written 34 books for children on some aspect of nature. After the Newbery, she published 91 more books (a few posthumously). Forgotten by most in the field, she kept producing because that was her niche, writing about nature for children. To me, she led an amazingly rich life. She gave me a book I truly loved and set me on the path to learn about nature.

Jean died at the age of 92 in 2012. When working on this article, I scoured my extensive children’s literature library for articles or essays by or about Jean. I found none. After her Newbery in 1973, it seems she fell off the radar. Before Julie of the Wolves was published, she’d already written 34 books for children on some aspect of nature. After the Newbery, she published 91 more books (a few posthumously). Forgotten by most in the field, she kept producing because that was her niche, writing about nature for children. To me, she led an amazingly rich life. She gave me a book I truly loved and set me on the path to learn about nature.

I’m still on it. Thank you, Jean.

A note from the Editor: A big thank you to Candice Ransom for sharing her deep knowledge of children’s literature with us through her many essays for Big Green Pocketbook and Bookology magazine. This is her final essay for this column.

We’re delighted to share that beginning with next month’s column, Candice will be writing about the illustration in children’s books and their illustrators in The Drawing Room. We’ve already read her first essay and it’s a doozy.

What a marvelous article, Candace. Thank you for it.