“What’s next?” kids — ask, as they whiz through life at warp speed. You’ve seen them constantly check their phones for texts, Snapchat, and Instagram. Kids at video game kiosks hunch over the controls, zapping animated figures and blowing up characters by the dozens. Should the adrenaline abate for even a second, they turn to the next game, in search of that high-risk rush.

Teaching writing for this video-visually-oriented generation brings the challenge of trying to hook them into picking up a pencil and writing their own stories, making themselves vulnerable to possible ridicule and teasing, compounding the state of perpetual self-embarrassment kids seem to live in for too many years in elementary and middle school. Before we can tackle this task, we need to identify our quarry — reluctant writers.

No doubt you’ve seen one of these “hate-to-write” kids. He sits at the back of a classroom, slumped back in his chair, his legs stretched out in the aisle, ready to trip the next unsuspecting kid. He glares at you — when his eyes aren’t glazed over, or staring out the window. He resists direction, gives you “attitude,” harasses substitutes, and, if you’re lucky, tosses spit-wads instead of chairs. Or maybe you’ve seen another “just-won’t‑write” kid. She also sits at the back of a classroom, her head often down on her desk, huddled over it in self-protection. She stares at you, first in fear, and then, almost as if a curtain has been drawn, with a blank look. She flushes with embarrassment if you call on her. She slides down in her desk, hoping that if you can’t see her, she’ll be invisible.

No doubt you’ve seen one of these “hate-to-write” kids. He sits at the back of a classroom, slumped back in his chair, his legs stretched out in the aisle, ready to trip the next unsuspecting kid. He glares at you — when his eyes aren’t glazed over, or staring out the window. He resists direction, gives you “attitude,” harasses substitutes, and, if you’re lucky, tosses spit-wads instead of chairs. Or maybe you’ve seen another “just-won’t‑write” kid. She also sits at the back of a classroom, her head often down on her desk, huddled over it in self-protection. She stares at you, first in fear, and then, almost as if a curtain has been drawn, with a blank look. She flushes with embarrassment if you call on her. She slides down in her desk, hoping that if you can’t see her, she’ll be invisible.

We who write and teach know that to be able to write is to set oneself free, but kids are terrified that they will be exposed and made fun of for what they write. Thus, it’s key to set the stage, the atmosphere, the expectations for writers as a community of mutual respect. If we want to liberate kids to be able to write in their own voices, they need to feel safe.

One way to do this is to jump-start the “voice,” by using an exercise with Little Grinda, Brat of the World, done in pairs. To begin, I tell them, “Some of you may not want to write because you think other kids will think you’re writing about yourself. Many times, as an author, I get asked, ‘Did that really happen to you?’ Here’s the answer to that: “No, no, and NO! Not really — and here’s why: Famous author Virginia Hamilton (M.C. Higgins the Great) once said, “Writing is what you know, what you remember, and what you imagine” — all three in one. It’s not about you and it’s not about me or about anyone you know — it’s a mash-up.” Sharing these ideas with the students helps to set the stage — to free kids up so they can begin to write with their own personal voices, which is, as you know, one of the critical keys to help kids connect with writing as not a dreaded process, but as a new adventure.

Put kids in pairs, and explain that voice is not who “they” are, but it is who their imagined character is. What is voice? It is like a secret trademark, and it can be serious, sassy, funny, or fierce. The words you choose, the audience you’re writing for, and your purpose all affect voice — BUT, it will always be unique, because it’s yours.

Then, we talk about the importance of verbs in writing with voice. In succession, I act out Little Grinda “slinking into the classroom,” Little Grinda “swaggering into the classroom,” Little Grinda “tip-toeing into the classroom,” and Little Grinda “stomping into the classroom.” We discuss how the different verbs inform the audience what Little Grinda is really like, and how differently we see her, depending on the verb. The verb does the heavy lifting in sentences. Besides using strong verbs, vivid, concrete details are also important to use in writing with voice, such as smell, touch, sight, sound, taste. Together in pairs, students will do the following exercise, being prepared to share with the rest of the class afterwards.

Little Grinda Voice Exercise

Write “jalapeňo” and not “oatmeal” by changing weak verbs to strong ones and by adding more concrete details to “show” the action, instead of “telling” it.

Little Grinda walked into the classroom. She looked at her classmates and smiled. She walked over to her desk and put her books down on the floor. She looked up at her Language Arts teacher Mrs. Whippersnapper and sighed. It was going to be another long day in Language Arts. She wrote a note to Clovis and folded it up.

Little Grinda walked into the classroom. She looked at her classmates and smiled. She walked over to her desk and put her books down on the floor. She looked up at her Language Arts teacher Mrs. Whippersnapper and sighed. It was going to be another long day in Language Arts. She wrote a note to Clovis and folded it up.

“Pass this to Clovis,” she said to Minerva. She then took her half-finished homework paper out and tried to smooth out all the wrinkles.

“Don’t you have your homework, Little Grinda?” asked Mrs. Whippersnapper.

“Of course I do, ma’am,” said Little Grinda. She tried to hide the blank half of the paper with her Hello Kitty pencil box.

“You know me and homework, Mrs. Whippersnapper,” said Little Grinda. Just then, the return note from Clovis arrived and Little Grinda put it in her sleeve.

“What’s that in your sleeve, Little Grinda?” asked Mrs. Whippersnapper.

“Oh, nothing,” said Little Grinda. All the other students began to smile and give each other knowing looks. “It’s just my Kleenex. I have a bad cold.”

“If you have a bad cold, you should stay home,” said Mrs. Whippersnapper.

Little Grinda just smiled, and all the other students began to whisper. They just couldn’t believe Little Grinda had gotten away with it again!

Once the students are done, remind them that it is important to remember when writing, and sharing writing, that consideration and respect are very important. Sharing writing is risky, so we need to be extremely respectful in the way we listen and comment.

Over the years in the classroom, I’ve found that the best format is to have kids respond to others’ writing by using this formula: “I liked….” and “I wonder what…” NOT “What were you thinking?”

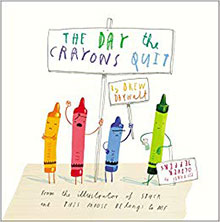

An additional voice exercise is to have them think outside the box: what if every object in the classroom were alive, such as the pencil sharpener … (ask for suggestions) Read aloud excerpts from The Day the Crayons Quit. Now, ask them to write two or three sentences — you ARE that object — write out what your feelings are as the first day of school approaches. Are you dreading it or looking forward to it? Then, have students read sentences aloud. Which verbs really added to the voice? Finally, ask students to choose one strong verb and one strong concrete detail or description from each work and begin their own verb bank lists.

An additional voice exercise is to have them think outside the box: what if every object in the classroom were alive, such as the pencil sharpener … (ask for suggestions) Read aloud excerpts from The Day the Crayons Quit. Now, ask them to write two or three sentences — you ARE that object — write out what your feelings are as the first day of school approaches. Are you dreading it or looking forward to it? Then, have students read sentences aloud. Which verbs really added to the voice? Finally, ask students to choose one strong verb and one strong concrete detail or description from each work and begin their own verb bank lists.

They’ll be on their ways to writing with their own voices, and, with any luck, not as reluctant writers!

[Sorenson-Margo-Bio]

Wow! Margo really hits the nail on the head with this artlcle – concrete ideas for teachers (parents and others, too), for encouraging authentic writing and voice. Love the “show, don’t tell” example. Bravo, Margo!